The Evolution of Blockchain for Bank Payments Modernization

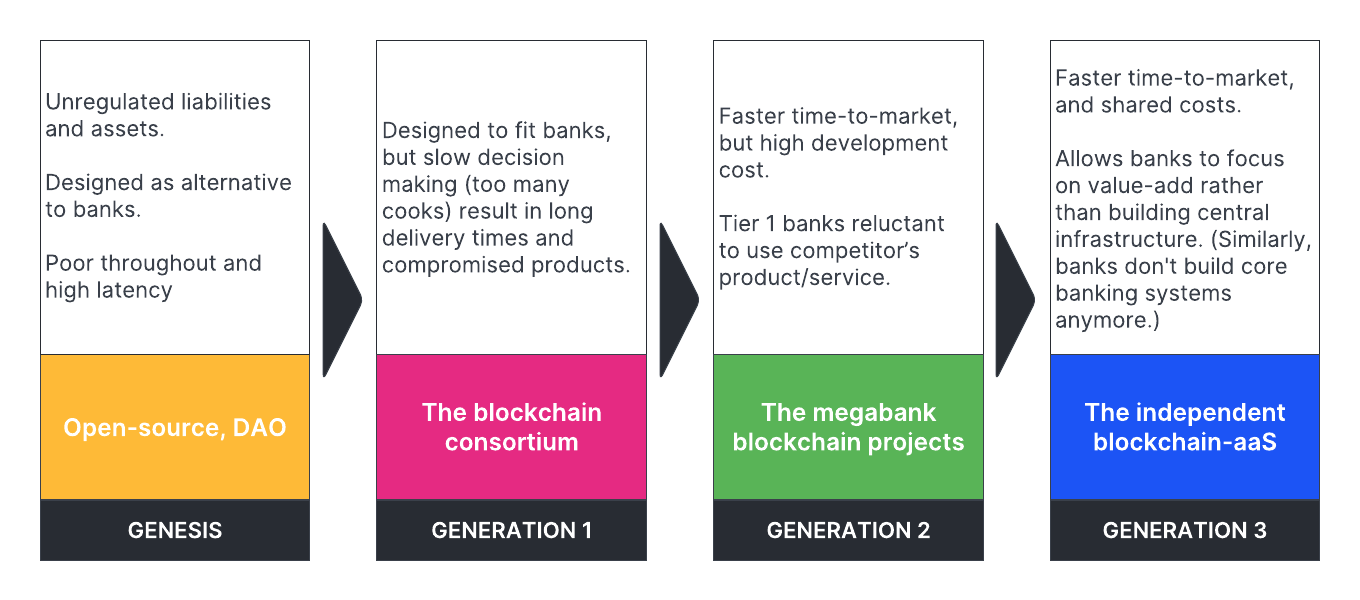

Blockchain: 1985-2014

The idea of cryptocurrency first emerged in the late 1980s. But it was only in 2008, when Satoshi Nakamoto published the white paper Bitcoin – A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System, that Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency, was realized. Cryptocurrencies were designed to be anonymous and have no central authority. Therefore banks, as regulated entities, could not use cryptocurrencies.

In 2012, Ripple was launched. The system was built upon a distributed open-source protocol, and using XRP, a Ripple-issued cryptocurrency. While Ripple had the aspiration that banks would adopt the system, the reliance on XRP was a nonstarter for banks. Ripple eventually introduced RippleNet, separating the Ripple messaging service but without the use of XRP or tokenization.

Where Ripple was a centralized, permissioned payment network, the Stellar network was launched in 2014 as an open, semi-permissionless network. Stellar Lumens, another cryptocurrency, act as a medium of exchange. In 2017, IBM announced that they would attempt to use the Stellar protocol to build a payment network for banks, but this was never completed.

The reliance on cryptocurrency as a medium of exchange for interbank payments was a hurdle banks could not get past. It wasn't until the focus on bank solutions shifted from cryptocurrency to the use of blockchain and distributed ledger technology to build bank payment infrastructure that blockchain gained traction with banks.

Generation 1: The blockchain consortium

The first of these initiatives was R3. Rather than focusing on the issuance of a cryptocurrency, R3 started as a consortium funded by HSBC and others in 2017. In 2018, they received additional investment from another 44 banks. The idea was for each bank to not only invest in R3 but to use the R3 technology to enable payments. However, the early R3 model assumed that the banks had the in-house technical resources to develop payment systems using the R3 technology. This proved to not be the case. Conceding this, R3 has changed its business model to partner with consulting firms like Accenture to take the R3 technology and build custom implementations for banks.

UBS funded some early research on what was called the Utility Settlement Coin Project. By 2019, this evolved into a consortium renamed Fnality International. Members included 15 multinational banks. Fnality has yet to launch a service.

The original concept of a consortium of banks building interoperable systems using common R3 or Fnality technology appears to have fallen by the wayside. None of the bank investors in R3 or Fnality appear to be actively supporting their activities.

The rise and fall of Facebook Libra/Diem is a fascinating illustration of the challenges facing a consortium. The initial Libra Association included Facebook, Visa, Mastercard, Stripe, PayPal, and several other technology companies. (Interestingly, neither digital wallet providers Apple and Google nor any banks joined the Libra Association.) Beginning in May 2018, this consortium funded the development of a digital coin tied to a basket of fiat currencies and securities. The project ran into regulatory headwinds and, in November 2020, was downsized to a set of single-currency stablecoins and later, only a USD denominated stablecoin. In January 2022, after a number of members left the Diem Association, it was decided to wind down operations and sell the intellectual property to Silvergate, a crypto-focused bank.

Generation 2: The megabank blockchain projects

With the demise of the consortium model, blockchain projects became the province of a handful of very large multinational banks. Perhaps the best known of these projects was the efforts of JP Morgan Chase and the launch of their JPM Coin in February 2019 (subsequently rebranded Onyx Coin Systems). This involves the creation of a USD stablecoin issued by JPMC.

The New York Times has reported that in 2020, “Bank of America filed the biggest number of patent applications in the bank’s history, including hundreds involving digital payments technologies. It’s unclear how exactly the bank plans to use its technology, but it was partly driven by the desire to keep customers within the bank’s systems rather than lose them to scrappy cryptocurrency start-ups that allow them to transfer money free.”

These megabank projects suffer from a number of limitations:

They are costly. Hence limited to only the largest multinational banks with a user base large enough to generate (or at least theoretically support) the necessary return on investment.

Blockchain engineers are generally not attracted to banks. While large banks may employ engineers, these are traditional engineers with backgrounds in relational database technology and conventional transaction processing. Blockchain experts are typically trained at blockchain companies and often leave to form new blockchain companies.

In some cases, large banks developing technology may be unwilling to license their technology to competitors.

Conversely, other banks may be reluctant to use the developing bank’s product. For example, it is hard to imagine a Citi or Bank of America using a JPMC-issued stablecoin and connecting to JPMC systems to process their payments.

Generation 3: The independent blockchain-aaS

Recognizing the limitations of a megabank project and the opportunities it creates, we argue that it is time for a new generation of providers. These providers would be independent of any single bank and technology-driven with expertise in both cutting-edge blockchain and the esoteric world of conventional payments.

Benefits

The Gen 3 provider enables:

Creation of a network of banks like Gen 1, but without individual banks having to do the development.

Faster time to market. The services would be delivered in a SaaS model.

Shared cost. Development costs could be capitalized and recovered across multiple bank customers.

Ease of integration into existing infrastructure. The new system would employ open APIs to enable easy integration into existing bank systems. These APIs could be integrated with key banking systems from vendors like FIS, FiServ, and ACI Worldwide. This means banks utilizing these systems would have an easier adoption path.

Implications for product

The emergence of a Gen 3 solution that can be shared across a network of banks has implications for the product/service:

Need for high throughput and low latency to easily serve today’s use cases and scale to tomorrow’s use cases. Target: 1M transactions per second at < 500ms latency.

Private permissioned DLT for speed and security with byzantine fault tolerant (BFT) consensus algorithm to deliver the highest system resilience and robustness.

Banks and payment service providers connect using APIs.

Payment information transparency for banks to meet regulatory obligations.

Optionally, provide regulators direct access to transaction information.

Implications for operations

It is likely that the Gen 3 provider will be a nimble, technology-first company. Exactly the kind of company that banks and regulators will have concerns about running critical financial infrastructure. As a result, we envision:

Trusted third-party operators will operate the Gen 3 platform - a local operator for each ledger. One ideal candidate for an operator would be the Payment Clearing House in a country. The Clearing House is often (a) owned jointly by the largest banks in the country, (b) has experience running key financial market infrastructure, (c) is already connected to the banks, (d) is trusted by the regulators, and (e) meets the data sovereignty requirements of many countries.

The role of issuing banks is unchanged in this model. The Gen 3 service acts as a parallel payment system. Issuing banks initiate payments (or requests for payments), hold customer funds, extend credit, provide customer service and reporting, and are responsible for KYC, AML, CFT, and sanction screening.

Implications for partnerships

Gen 3 providers may face challenges to engage decision makers at central banks and commercial banks. We predict that they would do best in establishing partnerships with leading technology suppliers who already provide software and services to banks. These suppliers are trusted and can stand behind the new Gen 3 provider. Some implications for these partnerships:

They will be non-exclusive. The value of the Gen 3 solution is interoperability. The goal is to build a network of banks. Different banks have different legacy providers and it benefits everyone if all the providers can offer the solution.

Leverage partners’ customer base and installed infrastructure. Enabling the partners' systems and software to support the Gen 3 APIs in advance shortens the time for bank implementation.

The message to Gen 3 providers and partners is: "don’t get greedy". There is enough for everyone and the opportunity is massive. Collaboration will lead to better interoperability and a higher chance of success as a result.